The interwar era was a key period in Australia’s criminal justice history, one that saw the rise of organised crime, gang violence and the narcotics trade. One of the individuals associated with this scene was Norman Bruhn. Bruhn’s prison record reveals a busy offender with 8 convictions listed against him. However, this only scratches the surface of Bruhn’s criminal history and connections.

Norman Bruhn – future gangster of both the Melbourne and Sydney underworlds – was born in Geelong on 2 July 1894. Victoria was in the midst of a severe economic depression following the collapse of the speculative land boom and the failure of several financial institutions. Norman’s parents – 31-year-old baker Oscar and 28-year old Mary Ann – already had four children. The eldest, Ellen, had been born on 30 October 1886, just four months after her parents’ marriage. William had followed in 1888, then Oscar in 1890 and Edward in 1893. Another five children were added to the clan after Norman’s birth: Stanley (1897), Agnes (1899), Eric (1902), Roy (1905) and Catherine (1908).

Perhaps, Norman Bruhn’s later criminality can be attributed in part to the example set by his father. Despite Oscar Bruhn’s status as an outwardly respectable small businessman and father of ten, several incidents suggest that he was a violent man. He was prosecuted in 1908 for throwing a rowdy spectator over a fence while umpiring a football match, for which he was fined 10 shillings. A newspaper report from 31 May 1909 stated that he had been arrested on a charge of assaulting his son William. Apparently, having arrived home to his house in South Geelong on 29 May in a vicious mood, Oscar threw a plate at his wife but missed her, then picked up William by his legs, swung him round and hurled him through a glass window. The boy escaped with only scratches; this was lucky for Oscar, preventing serious punishment. But worse was to come. In 1911, Oscar was tried for the indecent assault of a 22-year-old domestic servant at the Ballarat Supreme Court. Despite corroborative eye-witness testimony from the victim’s employer, and the employer’s nine-year-old son, Oscar was acquitted.

Norman Bruhn’s childhood was thus less than ideal: a violent father and, if not economic uncertainty, then at least little in the way of indulgence. By 1908, 14-year-old Norman was working at a woollen mills at Geelong when his arm was caught in the machinery and fractured. The next few years would see a few minor skirmishes with the law – riding a bicycle at night without a light in 1910 and offensive behaviour in 1914 – before Norman and three of his brothers enlisted during the First World War. Several of the Bruhn brothers were court-martialled during their service; Norman for being away without leave for several months in France in 1919. After serving a short sentence in England he was shipped home and discharged in early 1920.

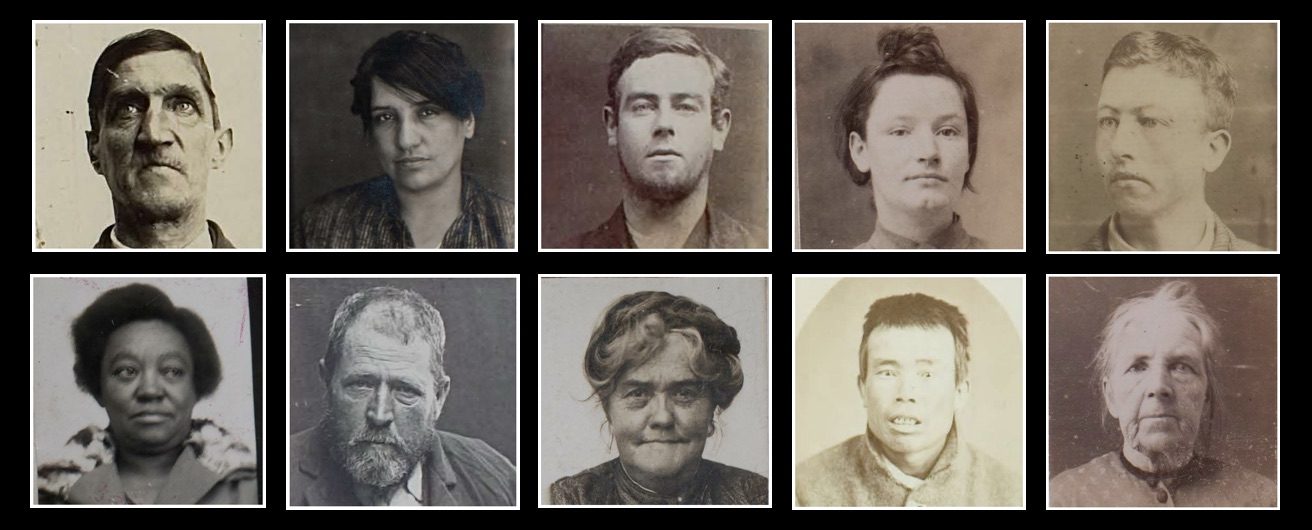

Mugshot of Norman Bruhn, circa 1921. Source: Public Records Office Victoria, VPRS 515/P1, item 71, page 258.

Thereafter followed a short, violent and active criminal career that spanned many types of charges: stealing; robbery; breaking and entering; loitering with intent; absconding on bail; assaulting police; obscene exposure; and being a suspected person. In some instances, convictions were secured, but on several occasions, Norman was acquitted or the prosecution against him was abandoned after witnesses changed their testimony (possibly as a result of intimidation by Norman or his associates).

Many of Norman’s offences involved co-offenders – including Irene Wyatt, an 18-year-old waitress he married in May 1920. At the urging of Melbourne rival Squizzy Taylor, Norman relocated to Sydney in November 1926, intent of assuming control of crime in the area around Kings Cross and Darlinghurst. Norman’s career was precipitately cut short when he was gunned down in Sydney in 1927. Although Norman survived for several days he famously refused to disclose the name of his shooter to police.

Well after his death though, Norman’s network of criminal contacts lived on and continued to offend. Prison and trial records can be used to trace these networks by mapping co-offending activity. In all, seven of the 19 incidents over which Norman was charged consisted of co-offences, which he committed with 14 different individual co-offenders overall. Norman’s 14 co-offenders in turn had 27 individual co-offenders of their own in the course of their criminal careers. These 27 individuals were then joined by a further 74 individuals who they co-offended with at some point. If the connections continued to be mapped, the circle would widen further.

Co-offending and co-offending networks have received little attention in historical scholarship to date. This is likely to change as more and more historical data is digitised, making it easier to map such connections across offenders’ lives and criminal careers. Given the significant role that social peers have typically been shown to have on criminal behaviour, co-offending is a topic that has long fascinated criminologists. One area of interest has been the extent to which members of co-offending networks tend to resemble each other, whether in social background, the types of offences committed or the length of time offenders engage in criminal activity.

The 116 offenders within Norman Bruhn’s co-offending network had a mean average of 7 convictions, although 44.8 per cent of the sample had only a single conviction. This was due to the presence of a number of highly recidivist individuals, with over twenty per cent of the sample amassing ten or more convictions. The average length of criminal career was six years, with 30 per cent of the sample having criminal careers of ten years or longer. The longest criminal career spanned 51 years from 1896 to 1948. While criminal offending within the network thus extended across a long period, 61 per cent of all offending was concentrated across the 1920s and 1930s, with much of this activity indicative of the network’s association with Melbourne’s violent gang subcultures.

Source: Herald, 25 May 1922, page 6.

Within Norman’s network, 62 per cent of offenders had at least one conviction for property offences, and more than a quarter had convictions for non-robbery-related violent crimes. However, much of the criminal activity of the highly recidivist offenders consisted predominantly of public order offences, particularly having insufficient means of support or using indecent language. Absconding on bail or escaping custody was another frequent offence, including two prison break-outs that involved multiple offenders. Some of the other offending activity is indicative of the socio-historic context of the time, including convictions for selling contraceptives, gambling and possessing illegal firearms, the circulation of which were a particular concern during the interwar period.

Contemporary co-offending research suggests that most co-offending activity occurs among offenders of a similar age, with intergenerational co-offending rarer. In the Norman Bruhn network, the birth years of offenders ranged from 1856 to 1916, but 49 per cent of the offenders were born in the 1890s, like Norman himself. Those born in the 1890s had a higher recidivism rate than those born outside of it, with 58 per cent amassing more than 6 convictions compared to 40 per cent of those born in other periods. The lives of this generational cohort would have been marked by a number of significant events: they were born in the midst of economic depression, came of age during the First World War and would have been workforce participants during the Great Depression, all of which likely factored into their criminal participation.

Only 25 of the 116 network participants were women. Women on average were connected to higher numbers of co-offenders than men. They were also more likely to co-offend with other women than men were, producing several hubs of female offenders within the wider network. Women in the network were more likely than men to be single-conviction offenders, but were also more likely to be chronic recidivists with a very high number of convictions. The offender with the highest number of convictions in the sample was a woman, Catherine Baker, implicated in 97 offences including several larcenies and one assault on police, although like most female recidivists the bulk of her criminal career consisted of public order offences. Like Norman Bruhn, Baker’s offending ended when she was herself a victim of robbery homicide in 1942, intimating an overlap between criminal offending and crime victimisation that was experienced by others in the network as well.

Similar to results in contemporary research on co-offending, the Bruhn network was mostly ethnically homogenous. Only three offenders were known to be of non-European ancestry: Joseph Wilson; Elsie Williams; and Agnes Barnes. Joseph Wilson was an Indigenous man born in Victoria, but both the women were born overseas. While Elsie was African-American, Agnes, born in Honolulu, was alternatively described as African-American or native Hawaiian. Elsie Williams had the second highest offending rate in the network, amassing 85 convictions over 16 years. Williams’ record included several serious assaults, with one of her final convictions over unlawfully wounding a married couple with a razor in concert with a white, male co-accused. This incident took place in 1939 at Dudley Flats, an area in Melbourne then supporting a large camp of people left homeless by the Great Depression. It was also poverty, rather than crime, that drew Wilson, Williams and Barnes together and into the network: in 1934 all three were part of a group of fourteen men and women arrested on vagrancy charges after being found living together in a Fitzroy flophouse.

Discerning the precise relationships between offenders in the networks is not always possible from the available sources, but a few general comments on what connected them can be made. Firstly, many of the offenders in the network were linked by a common geographic location, with 59 per cent of all offending activity occurring across the adjacent suburbs of Carlton, Collingwood, Fitzroy and North Melbourne, a total area of just 690 hectares. The bulk of the network was furthermore listed as being engaged in some form of manual labour, and may have met through work, particularly on the docks, which had known connections to Melbourne’s criminal underbelly.

Several offenders also had marital or blood ties to each other, with the most prominent family within the network being Norman’s own. The only family member known to have co-offended with Norman personally was his wife, Irene, who was subject to two counts of receiving stolen goods of which Norman was the thief. Two of Norman’s brothers also appear in the network, but not for co-offending with Norman directly. Known by reputation at least to run in the same gang as Norman, Eric and Stanley Bruhn entered the network via Arthur Collis, also one of Norman’s co-offenders. With 33 offences committed with 27 co-offenders over a 42 year period, Collis was far more prolific in both convictions and network contacts than any of the Bruhn brothers. Two other brothers do not appear in the network, despite being known to run in the same circles. These absences point to the utility of methodologies that overlap co-offending networks with kinship, social or organisational networks. In Norman Bruhn’s case this would reveal a continued legacy of criminality amongst his descendants, including grandsons Noel and Keith Faure, who were convicted of the 2004 murder of Melbourne crime patriarch Lewis Moran.