Although male offenders far outnumbered women, both historically and in the present, the lives of over 6,000 female offenders can be glimpsed through the prison records being transcribed by citizen historians for the Criminal Characters project. These female prisoners include infamous Melbourne prostitute-pickpocket Lily Walker.

Locally-born Lily Walker was first tried at the Melbourne Supreme Court in 1885, aged just 17 years old. Listed in her prison record as a brown-eyed brunette with a sallow complexion and a diminutive stature of 4 feet 10.5 inches, Walker was described in newspaper accounts of the trial as a ‘gaudily-attired female’. This coded language, along with references to her being a ‘notorious character’, served to inform the knowing nineteenth-century audience that Walker was a sex-worker.

Walker was charged with larceny from the person, known colloquially as pickpocketing. This was the most common felony that women were charged with during this period in Melbourne, accounting for around 24 per cent of all cases brought against women in the city’s superior courts. The vast majority of these cases (at least 88 per cent) involved women who had pickpocketed from men under the guise of soliciting prostitution. Surviving witness depositions make the circumstances of most cases reasonably clear, with many women themselves freely admitting that they had engaged in a sexual relationship with their accusers in exchange for money. While Walker’s prison record lists her trade as dressmaker, her frequent appearances in court on pickpocketing charges over the next three decades suggest she was deriving part, if not all, of her income from prostitution.

J. A. Panton, Esq., PM, 1904, Frederick McCubbin. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Gift of Mr Hugh McCubbin, 1960.

Despite its prevalence, female pickpocketing also had one of the highest acquittal rates, with 61 per cent of women charged with larceny from the person acquitted, compared to a 50 per cent acquittal rate among women charged with felonies overall. Walker was one of many women who benefitted from juries’ tendency to acquit in such cases. The five larceny convictions listed on Walker’s prison record were just the tip of the iceberg; newspaper reports reveal that she faced at least five other prosecutions on similar charges of which she was acquitted. In fact, Walker became well known for her ability to escape conviction. When she was brought up on pickpocketing charges yet again, Joseph Panton, who presided over Melbourne’s Court of Petty Sessions (today’s Magistrates Court) at the turn of the twentieth century, commented resignedly on the matter. As he noted in January 1903:

We have frequently sent up Lily Walker for trial with a knowledge that the case is pretty clear against her. It, however, appears to be of very little use, but it is our intention to persevere.

His words proved prophetic; Walker escaped conviction yet again on that occasion.

The association between pickpocketing and prostitution likely influenced its low conviction rate, due to the victim blaming narrative this engendered. Newspapers typically reported such cases in derisive terms, one paper describing a case in 1883 as ‘the old, old story’ of a ‘fool and his money’. Another reported the theft of a miner’s money by two women under the heading ‘A Stupid Digger.’ Some officials took a similar view. Following the 1874 trial of two women for robbing a man in a brothel, Melbourne Gaol Superintendent John Castieau noted that, while there was ‘no doubt’ of their guilt, they were acquitted after the judge, who ‘seemed to think it served the loser right’, summed up in the prisoners’ favour. At the conclusion of another case in 1902, Judge Hamilton likewise declared that ‘people who went about at that hour of night accosting strange women should not complain if the end of their adventures was not as happy as they had expected.’

Negative perceptions of male victims in pickpocketing cases may have resulted in a high rate of jury nullification, even when men denied that they had been with women for an immoral purpose. The reputational damage men risked in launching such prosecutions meant that the cases brought before the court represented only a small fraction of such crimes, with many reportedly reluctant to initiate criminal charges and risk the publicity of a trial. The Justice in Walker’s 1885 hearing in fact commented upon both the reluctance of men to prosecute and juries to convict in such cases:

In summing up his Honor told the jury that they were not there to vindicate the rights of the person. Probably in regard to the loss which had been sustained by the prosecutor, Barrett, their verdict would be ‘Serve him right.’ That would be his own verdict so far as the individual was concerned; but they were there to consider the Criminal Law….He did not hesitate to say that he believed this man Barrett [the victim], if he could have presented it, would not have appeared in this prosecution, having got his deposit receipts back; but the matter had got into the hands of the Crown, which said that such offences could not be committed with impunity, and therefore the Crown in such cases compelled people who made such complaints to appear and prosecute.

Despite the judge’s summation clearly favouring outright conviction, the jury returned a partial verdict of guilty of the lesser offence of receiving stolen goods. The 17-year-old Walker was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment on this occasion.

Another reason that female pickpockets like Walker often got away with their crimes was that they regularly worked in concert with other women to perpetrate them. Street-walkers often worked in pairs or groups so that one could act as a police look-out while others conducted business; this also meant other women could be on hand to act as distractions during robberies or help thieves fight off and escape enraged clients when thefts were discovered. Even if pursued by men or police straight away, women often had established systems for quickly passing off loot to their friends; if the money or goods was not found on the accused, a conviction was unlikely to result.

Lily Walker revealed a sense of sisterhood among such criminal women in 1897, when she was approached by a man who offered her money if she helped him identify two women who had robbed him a few days before. Declaring ‘us girls won’t put one another away’ she went on to rob the man of the money he had on him, passing it off to a group of women standing nearby who told Walker to run for it, while they kept the male victim on the ground. When she was later arrested by police for the offence, she appealed to women standing nearby to come and pay her bail. Pooling funds to cover bail and legal defence costs was another way in which the community among prostitute-pickpockets was likely instrumental to their high acquittal rate. At a time when a third to two-thirds of those accused of felonies were undefended at trial, it is notable that Walker appears to have never been without legal representation.

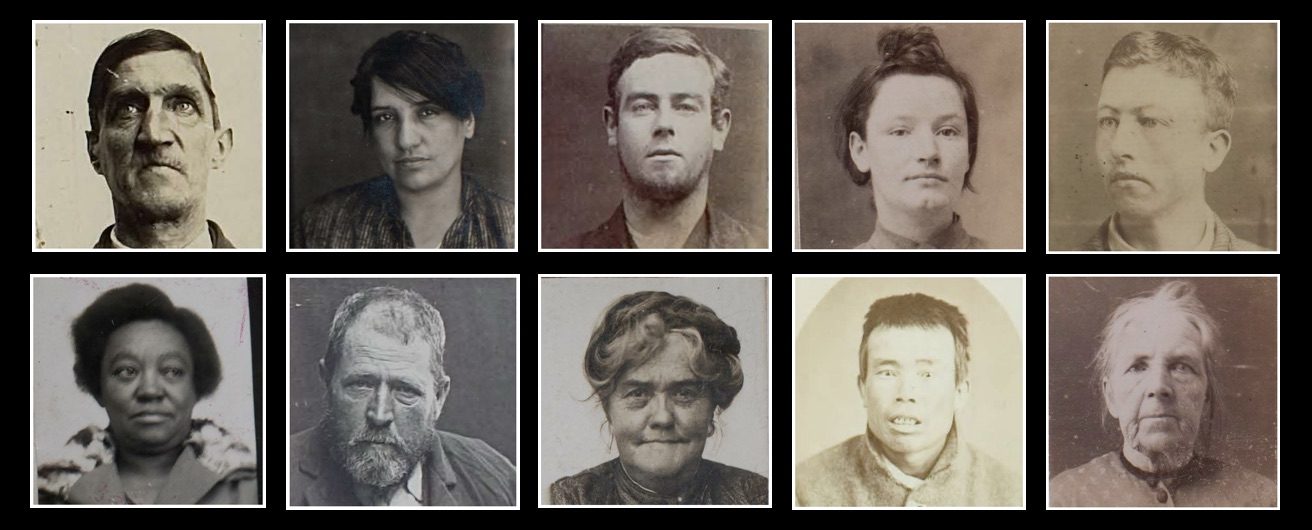

Mugshot of Lily Walker (alias Lillian Miller), circa 1913. Source: Public Records Office Victoria, VPRS 516/P1, item 12, page 190.

The police, when unable to convict women like Walker of more serious offences, often tried to remove them from the streets at least temporarily by charging them with minor public order offences. Walker thus served a brief sentence for vagrancy in 1898. However, by 1902, she had acquired the means to defeat such a prosecution. To sustain a charge of vagrancy, police had to demonstrate that an individual had no legitimate means of earning a living. To counter such assertions, Walker produced a healthy savings bank book, as well as a marriage certificate. She claimed that the various deposits noted in the credit ledger of the bank book were payments she had received from her husband, a miner in Western Australia. While this may or may not have been the truth, the difficulty of the police in disproving it meant that the prosecution against Walker failed, as did a subsequent attempt the following year.

In 1908, however, it seems that Walker had finally gone too far when, in the company of a woman named May Pearson, she pickpocketed clergyman Reverend William Barrie one night as he walked home. The assault was reported in newspapers as an ‘amazing outrage’ and evidence of an ‘epidemic of unbridled lawlessness’ in Melbourne.

At trial though, Barrie’s identification of the women, and his reasons for being out late at night, were called into question. As a result of these tactics, the jury failed to agree on a verdict. At the subsequent retrial, the prosecution pointed out that the nature of the evidence, which basically pitted Barrie’s testimony against that of the women, meant the clergyman himself was ‘practically on his trial, and that a slur would be cast against him if the women acquitted.’ The cross-examination of Barrie mirrored that of victims in rape trials, with questions about his level of resistance and insinuations of sexual misconduct:

You offered a stout resistance? – Yes. I called out ‘Police.’ I kept shouting it out. – And how long were you, a poor mere man, in the hands of this vigorous female? – For a minute or so. She did nothing but clasp me in her arms. (Laughter.) What for? – To take my money, of course.

After a lengthy deliberation, during which the jury returned to court to further question Barrie, a guilty verdict was returned against both Walker and Pearson. To the end Walker implied Barrie was at fault, proclaiming as she was taken from court “God will judge me and also you, Mr Barrie.”

The judge was determined that, this time, Walker would truly be made to pay for her crimes. In addition to imposing a sentence of two years hard labour, he declared Walker a habitual criminal, meaning that she could be detained indefinitely until authorities deemed she was reformed. In response to the sentence, she sardonically responded, ‘You have given me a nice birthday present your Honor. Thank you.’ Walker was eventually released from prison in 1913. In 1918, she was again convicted of stealing from the person, this time in Sydney. After that, no further trace of her has been found.

Further Reading