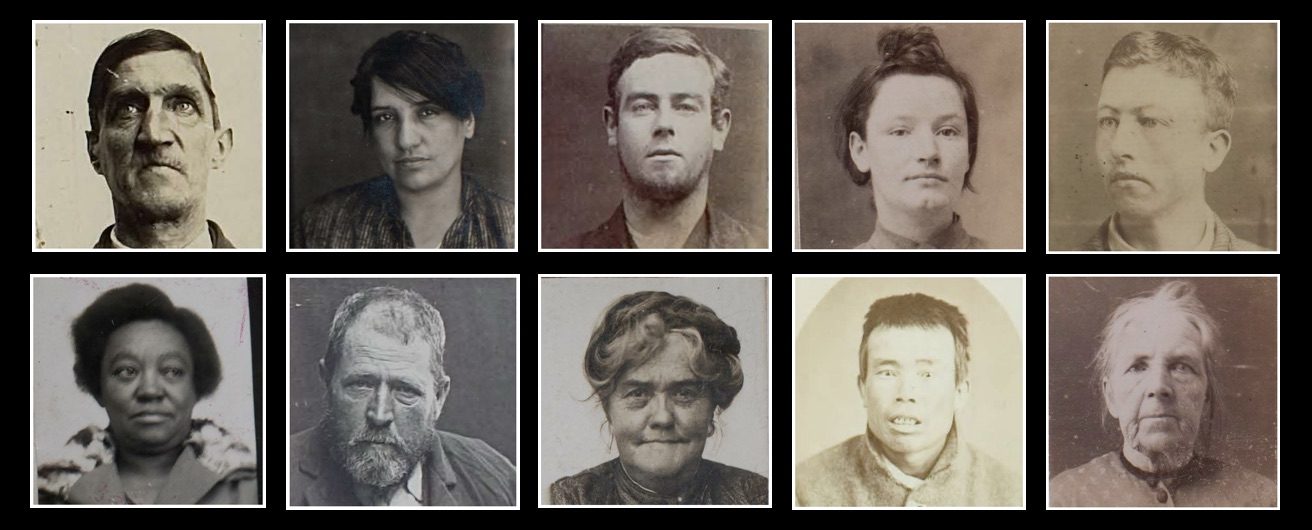

Prison records reveal fascinating, complex and often tragic human stories. Delving into almost any prisoner’s life will reveal points of interest, but some characters do stand out. William King’s record jumps out to viewers for two reasons. Firstly, its length: King was reconvicted multiple times, and committed more infractions against prison discipline than perhaps any other prisoner of the period. Secondly, King’s mugshots show his rapid deterioration from youth to old man, and draw attention to King’s African-American heritage.

Mugshot of William King, circa 1890. Source: Public Records Office Victoria, VPRS 515/P1, item 40, page 240.

King was not the only person of African descent in Australia during the nineteenth century, nor the only one to spend time in Victoria’s prisons. In her book Black Founders: The Unknown Story of Australia’s First Black Settlers, Cassandra Pybus found that there were at least a dozen convicts of African heritage on the First Fleet when it landed in Sydney Cove in 1788. She also discovered that Australia’s first bushranger was an escaped black convict, Caesar. Pybus notes that in later years, African or African-American men often arrived in the Australian colonies as sailors.

King’s prison record lists him as a cook, though he is described elsewhere as a sailor. Possibly he worked as a ship’s cook. Later, his prison record was updated to give his occupation as mason. Other details about King’s life revealed in his prison record include that he was born in America in 1863, that he arrived in the colony on the ship Carthage in 1887, and that he could both read and write. His religion was initially listed as Roman Catholic, but was later updated to atheist.

An Ordinary Criminal

In some respects, King represented the typical offender of the period. He was male, working class and lived in the urban centre of Melbourne. He began offending in his early twenties, and most of the 12 offences with which he was charged between 1888 and 1911 were property crimes, principally housebreaking. It was largely King’s career in prison that were to make him an infamous public figure during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

William King was first imprisoned in 1888 for burglary on a sentence of eighteen months’ hard labour, convicted under the name William Frazer. During this relatively short stint in Melbourne Gaol, King was punished for an infraction of prison discipline only once. For using improper language, he was given four days close confinement on half rations. (Close confinement involved a prisoner being kept apart from other prisoners, but in an ordinary cell rather than a solitary confinement cell.) Released in September 1889, less than twelve months later King was sent to Pentridge Prison on a combined sentence of nine years and six months for four convictions of receiving stolen goods.

Section of William King’s prison record, listing just some of the infractions of prison discipline for which he was punished. Source: Public Records Office Victoria, VPRS 515/P1, item 40, page 240.

During this detention, King committed 53 separate infractions of prison discipline. Perhaps the prospect of such a long sentence left King with feelings of hopelessness and aggression. Perhaps the colour of his skin resulted in hostility against him, or increased the perception that he was a dangerous offender in need of rigid discipline and control. King’s infractions mostly consisted of things like ‘insolence’, ‘disorderly conduct’ or ‘disobedience of orders’. They were punished by periods of solitary confinement or being kept in irons, with the latter on one occasion for a span of nine months.

A Celebrity Criminal

By 1897, King’s behaviour started to attract media attention. Initially these articles, given titles such as ‘A Troublesome Convict’ and ‘A Dangerous Criminal at Pentridge’, vilified King, describing him as ‘a notorious and powerfully built negro culprit’. However, by the end of 1898, some newspapers started to suggest instead that King was a victim. In December 1898, socialist newspaper The Tocsin ran a long exposé entitled ‘Torturing a Negro at Pentridge’. This related a lengthy statement from an anonymous informant (most likely a former inmate) alleging that the prison warders deliberately targeted King by giving him baseless punishments and by ganging together to give him beatings in his cell at night. The informant further revealed that King had long maintained his innocence of the offences for which he had been convicted, claiming he was a victim of racial prejudice. The newspaper divulged that the multiple punishments inflicted on King meant that he had been spending more than one hundred days of each year in solitary confinement.

Source: Argus, 8 December 1898, 5.

These disclosures prompted political interest in King’s case. During the sittings of the Legislative Assembly, Victoria’s Chief Secretary Sir Alexander Peacock was asked if the account of the cumulative time that King had spent in solitary confinement was correct. Peacock conceded that they were, but justified this on the grounds ‘King was a very bad case, and there was no power to flog for prison insubordination’. However, The Tocsin continued to exert pressure by publishing further articles on King that maligned Peacock, the prison administrators and the practice of solitary confinement in general. Although King’s sentence had been extended as a result of his infractions, in April 1900 he was released to freedom by ‘special authority’, perhaps a decision partly motivated by the sympathy King had started to arouse.

King was convicted again on two counts of burglary just six weeks later. The trial was made more sensational by the revelation that in one of the burglaries a young woman had awoken while King was ransacking her bedroom, and had allegedly threatened her with sexual violence. In a statement to judge William Gaunt prior to sentencing, King asserted that he would ‘rather be hanged’ than return to prison. He went into detail about mistreatment he received in prison, then declared that he had been persecuted by police from the moment of release, and been scapegoated by them for the crimes.

One of the detectives who worked the case and testified against King, David George O’Donnell, later recalled King in his memoir, describing him as ‘a big, burly, repulsive looking American nigger….absolutely dangerous to life and limb and especially to the life and limbs of women’. While this suggests that prejudice factored into attitudes towards King at least to some extent, the trial judge was dismissive of such claims. He gave King a cumulative sentence of ten years’ imprisonment with hard labour, and ordered that he spend the first week of the first, third, fifth and eight months of the first and third years of the sentence in solitary confinement.

A Habitual Criminal

In the final four months of 1900 alone, King was punished on 17 occasions for misbehaviour inside prison. His misconduct record continued to rapidly expand across 1901 and 1902, but thereafter the frequency of such incidents declined. In view of his good conduct, King was granted early release from his sentence in July 1908. Again, freedom was short-lived. In August, King was convicted of one count of burglary and one count of stealing in a dwelling. This time he was not only sentenced to 15 years hard labour, but declared a habitual criminal. Under the 1907 Indeterminate Sentences Act, courts in Victoria were empowered to detain such habitual criminals indefinitely.

Mugshot of William King, circa 1908. Source: Public Records Office Victoria, VPRS 515/P1, item 40, page 240.

By this time, King’s prison record was so full that administrators needed to start a new entry for him. This new record quickly began to fill up with more infractions and punishments. Furthermore, in February 1909 King was tried for wounding with intent to do grievous bodily harm after he stabbed prison guard William Sharp in the cheek with a knife. King claimed in court that it was Sharp who had brought the knife into the cell, and he had been stabbed as King was trying to get it away from him. His statements at this point show some signs of mental disorder, with King contending that he was a prince from Central Africa and asking to be allowed to go free so that he could build a flying machine that he would gift to the government before leaving the colony.

As a result of the stabbing, King was ordered to spend the first fifteen days of the third, seventh, eleventh and fourteenth month of his sentence in solitary confinement. King also continued to receive other terms of solitary confinement for unruly behaviour. In March, the medical officer of the prison, Dr Stewart, raised concerns that King was not in a fit mental state to undergo further solitary confinement. Victoria’s Premier, John Murray, asked for information on King’s condition from two medical experts, who reported back in April that King had lost ten pounds during his most recent seven-day solitary confinement, and was generally debilitated. They did not consider him insane, but stated that he was not fit to undergo any term of solitary confinement. The following week the government announced that they had stayed the use of solitary confinement against King for the time being, referring to the deleterious effects solitary confinement had been found to have in general.

This ‘experiment’ in discipline was declared a failure in November when it was reported that King stabbed another warder. At his trial for this offence in February 1910, King’s defence was that on the morning in question he was held down and beaten by five prison warders, including the one who he was accused of wounding. After several blows he had managed to draw out a knife that he kept concealed on his person. In response to a question from the prosecutor George Dethridge, King declared that he would rather be hanged than return to gaol. Indeed, if King’s version of events about the beating was untrue, this may have been the motivation for King’s attack on the guard.

A Violent End?

Mugshot of William King, circa 1915. Source: Public Records Office Victoria, VPRS 515/P1, item 60, page 277.

In March 1911, King appeared before the court yet again charged with the attempted murder of a prison guard, his final and most serious offence. One prisoner who witnessed and intervened in the violence testified that two days earlier he had heard King say that he was going to kill ‘some bloody bastard’ so that he could be hanged, as he could not endure 15 years in gaol. In a lengthy statement to the jury, King admitted committing the assault, but stated that his intention had not been to take a life but to be placed on trial so he could disclose to the public the abuses he had suffered at Pentridge.

He claimed that he was a victim not only of brutalities by the guards, but other prisoners. King referenced in particular violence he had suffered following the outcome of the 1910 Jack Johnson-Jim Jeffries boxing championship, a match between an African-American and white competitor dubbed “The Fight of the Century”. It resulted in race riots in the United States when the African-American Johnson knocked out Jeffries, an event captured on film and reported around the world. King again asserted his innocence of several of the crimes he had been convicted of in the past, declaring that he was not the ‘desperate and dangerous criminal’ that the newspapers depicted him to be. He asked the jury to remember that he was a ‘black man and alien’ in Australia, with no one able to assist him in his troubles. It seems this speech succeeded in arousing the jury’s sympathy: they returned a verdict of not guilty.

King was returned to prison to complete the rest of his sentence, which apparently proceeded much more quietly, with no further notations for prison infractions. In view of this, in February 1916 the order was given for King to be released upon the condition that he be deported to the United States. Police escorted King on board the ship Puacko, which was bound for San Francisco. According to the reminiscences of Detective O’Donnell, the Captain then told King this:

Look here, I’ve heard some bad accounts of you, and I want to tell you if there is going to be any trouble aboard this old sardine box, caused by you, on the voyage to ‘Frisco, you just look out. There aint no coroner’s inquests aboard this here packet and if you’re agoing to cause any trouble, you’ll go down to Davy Jones’s Locker. Do you get me?

Notification was later received that King had died at sea on 7 April 1916 of a stomach complaint. Prison authorities stuck a newspaper report of the death into King’s record.

King’s story is unique in its particulars, but in other ways is fairly standard in the questions it leaves unanswered. Delving into the life stories of historical offenders almost inevitably reveals complex characters, whose experiences might be interpreted as having proceeded from villainy, victimisation or some mixture of both. Whether examined individually or as part of larger patterns and trends, these narratives offer significant insights into the historical development of social and legal cultures.

If you found King’s story of interest, consider dedicating some time to transcribing other prison records as a Criminal Characters volunteer.