Fortune-telling was a criminal offence under legislation inherited from England, specifically the Witchcraft Act 1735 and Vagrancy Act 1824. Fortune-telling later became an offence under section 9 of Victoria’s Police Offences Act 1907, which read:

Any person pretending or professing to tell fortunes or using offence – any subtle craft means or device by palmistry or otherwise to defraud shall be liable upon conviction to pay a penalty not exceeding Twenty-five pounds and in default of payment to be imprisoned for any time not exceeding six months.

Despite being illegal, fortune-telling was seldom prosecuted in the Australian colonies during the nineteenth century.

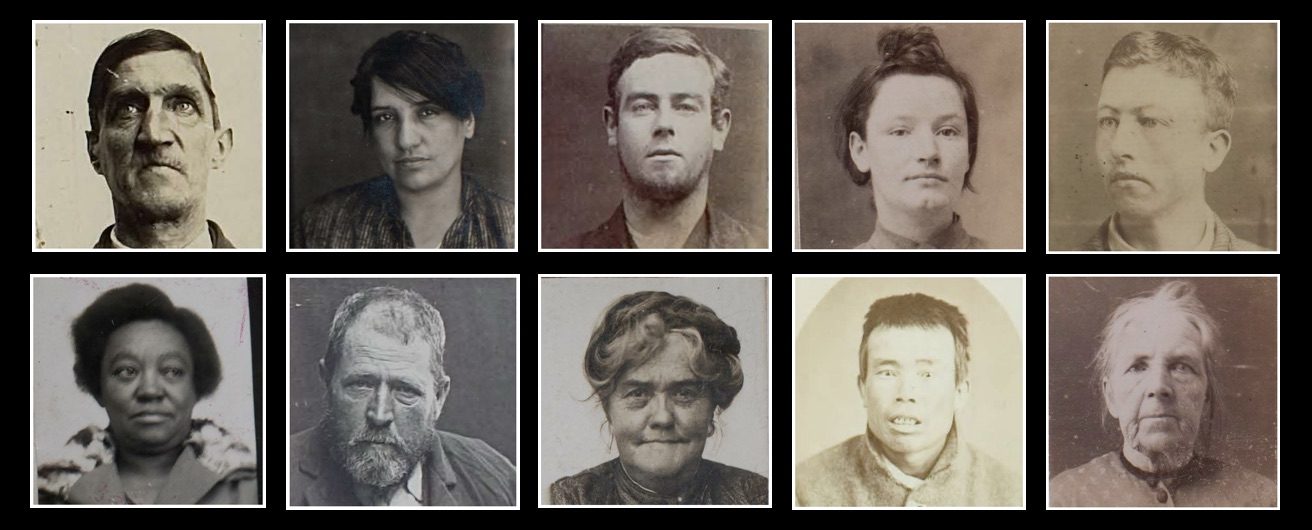

This changed in the early twentieth century, when the growing popularity of fortune-telling as both an entertainment and a spiritualist practice led to a moral panic and series of police crackdowns. Concerns about fortune-telling activity were stimulated not only by the perception of it as a form of fraud, but by claims that practitioners dabbled in other illicit practices, including abortion and white slavery. Fortune-telling was moreover the subject of prejudice due to its association with women, the working classes and people of colour. This resulted in waves of police prosecutions, particularly during the First World War under the impetus of Australia’s newly-minted women police officers.

However, magistrates were usually sympathetic to those who appeared on such charges, many of whom were deserted wives and mothers who turned to the trade to support themselves or their families. If convicted, most were sentenced to small fines or imprisoned until the rising of the court (i.e. until all the cases that day had been concluded). Given these light penalties and the attractiveness of fortune-telling as an income stream that women could generate from home with little start-up costs, many women continued to engage in the business despite charges being sporadically laid against them.

The most notable of these women was Sydney fortune-teller Mary Scales, whose popularity among an upper-class clientele in the early 1900s helped her amass a sizeable fortune. Scales was also significant for successfully challenging the legality of the fortune-telling provisions in the 1907 High Court case Mitchell v Scales, on the grounds that the 1824 Act had not been properly received into the law of New South Wales. This was a short-lived win, with New South Wales along with all the other Australian states criminalising fortune-telling under the various Police Offences Acts introduced across the 1900s and 1910s. Although seldom invoked, these laws remained on the books until the early twenty-first century saw their widespread repeal across Australia.

Further information:

Hume, Lynne. “Witchcraft and the Law in Australia.” Journal of Church & State 37 (1995): 135-50.

Patrick, Jeremy. Faith or Fraud: Fortune-telling, Spirituality and the Law. British Columbia: University of British Columbia, 2020.

Piper, Alana Jayne. “‘A menace and an evil’: Fortune-telling in Australia, 1900-1918.” History Australia 11, no. 3 (2014): 53-73.

Piper, Alana. “The scales of justice.” Criminal Law Journal 38, no. 6 (2014): 384-386.

Piper, Alana. “Women’s work: The professionalisation and policing of fortune-telling in Australia.” Labour History no. 108 (2015): 1-16.